On this Page

In the 19th century lace making was an important source of income for ladies living in the local villages. The 1851 census shows that of a female population in Lacey Green of 104 over 7 year olds, 80 were engaged in making lace. By the 1881 census that number had increased to 136, and 39 in Loosley Row. Lace making probably came to our part of England with protestant refugees fleeing religious persecution in the north of France, Belgium and Holland.

For modern day workers like myself, lace making is a fascinating craft. We enjoy the challenge of conquering another form of handwork. However, for Victorian workers it was far from enjoyable. It filled every spare moment of their waking life but after the invention of lace making machines, no matter how hard they worked, they could no longer make a living. The first lace making machine was invented in the 1770s, and mechanisation had become well established in Nottingham by 1830. It is the history of lace making after this date and especially towards the end of the 19th Century, which has particularly interested me.

It is almost certain that lace was made in our villages in the 18th Century and perhaps even in the 17th Century but I have not found any records of this. In the early days it would have been a much better paid occupation. Then all lace was handmade. To encourage the local workers imported lace was highly taxed, which lead to a flourishing trade in smuggling.

There is evidence that lacemakers earnt about 6d per day when the price of a loaf was just over 1d.

As always the poor were at the bottom of the heap. They were dependant on others to provide them with orders and supplies, and these people also took a cut of the profit. Suppliers might work through local shops or be itinerant peddlers, coming back after a set time to collect the work. When bobbin lace making was seriously in decline a local wealthy lady might arrange orders for the villagers.

Suppliers would provide suitable threads and patterns known as "prickings". Workers would probably only learn to make a few patterns, so that they could work faster.

In 1830, High Wycombe and Princes Risborough had lace dealers who sold thread and bought finished lace. They also carried a range of goods, to exchange for lace.

Toward the end of the 1800s in some lace making areas, wealthy ladies, who lived in large country houses, were aware of the poverty around them. Many tried to help the village lace makers.

One such was Mrs Eveline Forrest who lived at Grimsdyke Lodge. We know of her work from a special investigation made by a Mr. A. S. Cole from the Victoria and Albert Museum. He was sent by the government to "salvage" the lace industry. In November 1891 he reported:-

I may be allowed to add here some particulars which I have received through correspondence with Mrs. Forrest, who resides near Princes Risborough, regarding 'Lacemaking at Lacey Green, nr. Risboro', Bucks'.

The means of producing and supplying lace makers at Lacey Green with new and well drawn designs rests in the main with Mrs. Forrest, and all the lace made to order, except what may be ordered by dealers for shops, passes through her hands. There are about 20 to 30 workers employed at Lacey Green, and were the trade to revive, there may be as many more. The average earning is not over 6d.(pence) a day. No children are being trained to the industry. As regards designs for lace, Mrs. Forrest's endeavour is to reproduce old patterns, which she regards as "far more beautiful in every way". She possesses several very perfect prickings, which must be fifty years old and which have never yet been worked for the sole reason that no purchaser can be found, and also, ladies will not wait to get a length made, which in the case of fine lace "must take time". The specimens of lace, which Mrs Forrest lent to me to look over, were narrow edgings of point net ground Bucks lace in which the headings or objects were repeated over and over again, as in lace from other places I visited. There were coloured coarse laces, suitable for curtains and trimmings to household linens, and similar to the kind of coarse lace made (however with greater variety of pattern) in Le Puy and in Bohemia..

Other sources of information also speak of Mrs Forrest's work. The handwritten minutes of the north Bucks Lace Association Committee Meetings (undated) record:-

Mrs. Forrest, a devoted friend of this organisation, has encouraged the revival for the past 15 years in Lacey Green. She is partial to the fine old Bucks designs which she considers equal to those worn a hundred years ago by our ancestors... ..Her workers undertake, from the finest Bucks at one guinea a yard, to narrow torchon at two and a half (old) pence a yard, without discarding Duchesse or Maltese. They use, from the finest Honiton (cotton) to the coarsest linen threads.

Harris's flax linen thread is invaluable for the new and cheap art coloured lace intended to match the embroidery of linen curtains, teacloths and bedspreads, eagerly sought after, often by old women with failing eyesight and trembling hands. True, for many engaged in household work the earnings are scarcely over 3 shillings per week, but often the sum is a real windfall considering it has been gained with moments otherwise lost.

An account of Buckinghamshire Lace Making written in 1900 by Miss M. E. Burrowes, first secretary to the north Bucks Lace Association, which organised the industry, states:-

We have among others: Mrs. Forrest, Lady Thistleton Dyer and the late Duchess of Buckingham and Chandos, The Countess Spencer and Mrs. Nind, to all of whom we are deeply indebted for the basis of the recent revival of Bucks lace trade, now some 20 or 30 or more years ago; and many are now working with success on the foundations of their good efforts and, we trust, that interest in real and well made lace has come to stay in England at least. And we can almost say that at the present the demand for good lace is greater than the supply but there is still much uphill work before its supporters and promoters, for many reasons...

Unfortunately, the latter part of this account is missing.

Other information has been gleaned from undated or unnamed newscuttings and hand written notes.

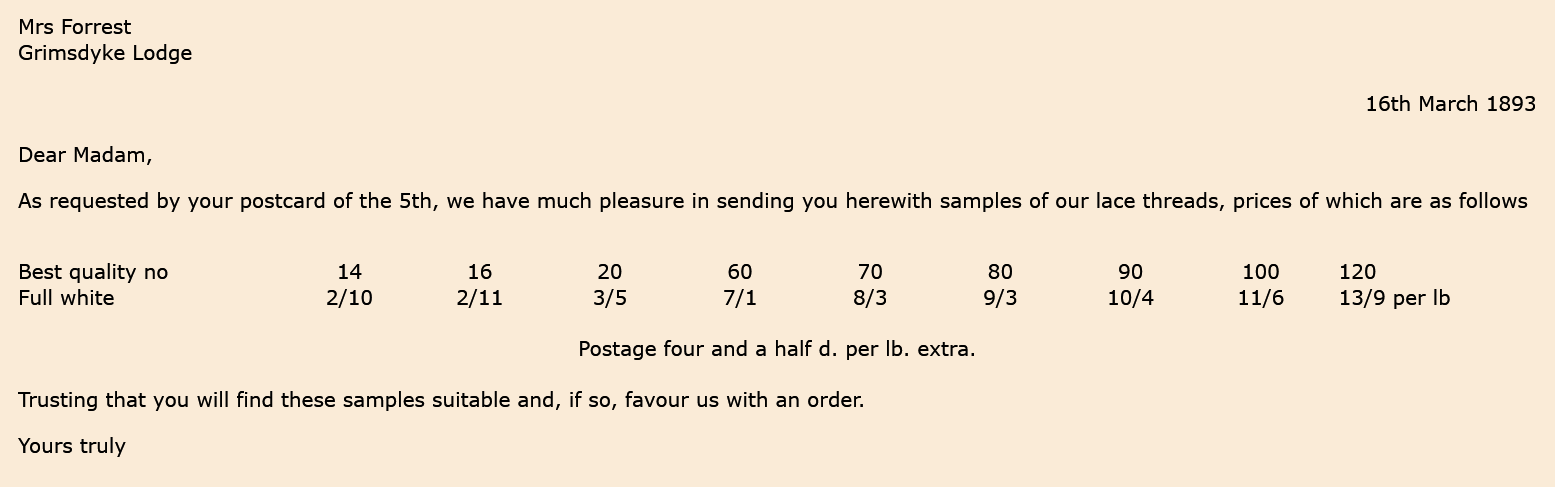

Although Mrs. Forrest did not supply threads, she wrote to William Barbour & Sons of Lisburn, Ireland, requesting information. The letter of reply is now in Aylesbury Museum.

Mrs Forrest taught needlework at Lacey Green and Loosley Row schools. She also heard singing in the schools.

Kathleen Church reported that the Forrest's regarded themselves as leaders in the community. Many people worked for them at a time when it was hard to find jobs, so it did not pay to upset them. Bill Dell's parents were married on the day of Mr Forrest's funeral. The event was so important that their wedding had to be postponed until later in the day. They told Bill that this was typical of Mr Forrest. A past resident of the village Mr. Harry Church remembered watching the funeral procession from the school widow.

The Local History and Chair Museum in High Wycombe and the County Museum Reserve Collection at Halton have lace samples from Lacey Green. These are labelled with the name Mrs. Forrest, and often priced per yard. Later, Mrs T. M. Forrest (possibly the daughter-in-law of Mrs Forrest, who had three sons - Charlie, Frank and Guy) gave a large collection of lace samples to the museum, but no information was supplied with them.

Mrs. Forrest was somewhat unusual in trying to help local lace makers to market their lace through the Lace Associations. Most ladies were simply patrons and gave an annual donation to support lace sales. Sales or Exhibitions were held in the large houses of these wealthy patrons, frequently in London.

Another sales outlet was the Annual Exhibition held in Oxford Town where there was a competition to encourage the making of lace. The report below comes from the Bucks Free Press, dated 31st. July 1892.

Oxford Self Help Association

At the annual exhibition held by this association at Oxford on June 2nd. and 3rd.1892, among the successful exhibitors for pillow laces made by the cottagers in Oxon, Bucks and Berks, and we are glad to observe the names of several of the pillow lace makers of this village (Lacey Green).

In the first division (the laces over 3 inches wide) Mrs Moses Hawes obtained a second prize for a copy of an ancient black silk lace and Mrs. Simeon Smith a third prize for an art lace (Cluny design) in coloured flax thread.

In the second division for laces over one inch wide, Mrs Moses Hawes was again successful gaining first prize for a lace the design of which is said to date from the time of Queen Elizabeth. Mrs Denning (Loosley Row) obtained a similar distinction for a handsome lace of old Buckinghamshire design. Mrs Tomkins and Mrs Peter Gibbons (Speen) both gained third prizes in this division, and the laces of Mrs. Losley and Mrs John Adams were commended.

In the third division for laces under one inch wide, Mrs John Currell gained first and second prizes, Mrs Codgell (North Dean) a second prize and Mrs Tomkins a third prize.

From the above very satisfactory results of this exhibition, as far as the cottagers of Lacey Green, Loosley Row and Speen are concerned, it is to be hoped that the revival of lace making which has lately taken place to some extent in this village, as in many others, may steadily progress and prosper.

A news cutting from Oxford Town Hall on May 25th to 27th 1900 states:-

An exhibition of Buckinghamshire pillow point laces was opened by HRH Princess Louise. Attending were Mrs. Forrest, Miss Sivewright, Miss Dewar, Miss Pope and Miss Burroughs.

This must have been the Mrs Forrest from Lacey Green. Miss Sivewright and Miss Pope of Headington supported the Thame District Industry. Miss Burroughs represented the North Bucks Lace Association. Miss Dewar's interest is not known.

It was usual for the ladies who helped the lace makers to have a sample of each lace offered for sale. They would show these to friends and encourage them to purchase lace. Mrs Forrest's samples are marked "Please return to Mrs Forrest", which indicates that these were lent to would be purchasers.

Mary was related to Dennis Claydon. She was born on 11th June 1843. In the 1851 census she is described as a lace maker, aged 7 years. In later life, her son Albert John is known to have turned her bobbins out of plum wood.

Charlotte was born about 1854, and is also listed as a lace maker in the 1881 census.

Clara gave an interview to "Buckinghamshire Interest" in 1955. She states that she has been making lace for over 60 years. Her efforts, when young, helped to eke out the family budget but she never made lace for a living.

Her mother learned lace at the age of 5 and her grandmother made "real old Bucks lace" at half a crown a yard for the Countess of Buckinghamshire.

The Wycombe Observer, in the 1960s, stated that Minnie had been making lace for over 70 years. She began at the age of 8 when a yard of lace cost two pence halfpenny. When she was 13 (around 1903), the Squire's wife (possibly Mrs Forrest) bought some of her lace and entered it in a competition where it won first prize. Her father used to make the bobbins. She mostly made lace for Mrs Tighe of Loosley House. Mrs Tighe paid one and a half pence per yard.

Minnie was taught to make lace by her mother Ellen. Ellen was widowed when Minnie was only 8. Money was very tight. The first Christmas they had only a bowl of rice pudding to eat. They both spent every evening lace making by candlelight to make enough money to live. Minnie said that every now and then her mother's bobbins would stop, and she would nod off for a few moments. Minnie and her mother kept a shop in the back room of their house (Bellvue Cottage).

She said that she had made lace incorporating gold thread but no examples remain. There is no evidence that she ever made coloured lace. After her death no coloured thread was found on her bobbins.

Ellen and Minnie also did bead work. In later life, Minnie specialised in making handkerchief borders for brides. Her daughter Phyllis still has a number of examples in traditional Bucks patterns like Duke's Garter and Water lily. She made proper shaped corners and often did her own drawn thread work on the handkerchief. Minnie made 16 yards of lace for her daughter's wedding veil. This has since been cut up for her grandchildren's christening gowns. What a labour of love!

During the second world war, Phyllis worked at Bomber Command, making maps on thin cotton fabric. Later her mother used this to make the hankies for her lace edgings, once the pattern had been washed off.

In an article from August 1930 entitled "A Vanishing Craft":

Mrs Mary Janes, lace maker, of Loosley Row has been making lace for over 60 years. She is now 68 but her clear complexion, the brightness of her eyes and the speed with which her fingers intertwine the threads upon the pillow, all belong to a younger age.

"Of course, it is simple to me after making lace all these years" she said, her fingers flying. "My mother taught me and I have been making lace ever since. The craft has been in my family for generations. My Grandmother made exquisite patterns, and I believe taught my mother". While she spoke, the bobbins rattled on, their threads weaving round a tiny forest of pins pricked in the pattern.

(n.b. This is a popular misconception amongst those watching lace makers at work. In fact the stitch is made first and the pin then put into position in the pricking to hold the work firm while the bobbins are still pulling on the thread. The pins may later be removed).

Mrs Janes can remember a time when lace passed for currency at the village store.

"In those days", she said, "good lace was appreciated. There was no finer lace in the land than Buckinghamshire lace. All we lace makers were proud of our craft. I remember that we could buy a week's supply of groceries from shops in the villages around in exchange for lace. We used to sit for hours and hours building the pattern up and then go off to the Bobbin Castle - our name for the shop in High Street, High Wycombe - to sell the lace".

But if Mrs Janes had to rely upon lace making for her food today, she would often go hungry, for few workers earn more than two or three pence an hour.

When Mrs Janes is working upon her most intricate patterns, she has six inches of lace after three weeks incessant toil.

"Lace of that kind is hardly ever begun now," she says, "Ladies don't appreciate it today. There was a time when the social standing of a woman was measured by the quality of the lace she wore. Those days are past. There is little or no market for handmade lace now. It would be impossible to make a living at it. I only make it occasionally for exhibitions and when a few orders come my way".

Years ago, lace makers used to buy their patterns, but now, one maker copies them from another. These patterns have the curious names of 'etches'.

Grandmother of Daphne Bristow. She is known to have made "coloured" lace. Her family originated from the lost hamlet of Coombs (between Lacey Green and Loosley Row). She eventually went blind, so perhaps the colours helped her to see the work when her eyesight was failing. Daphne's mother and aunt also made lace. Some of her mother's bobbins had her sons' names on them.

When Daphne was a schoolgirl (about 1920) she remembers three old ladies who used to meet in each others houses for the morning, while the children were at school. They took a sandwich, had a chat, and made lace for sale. They spoke of making lace for the trousseau of Lady Sydoney, daughter of the Earl of Bucks.

The Free Press has several reports of lace makers taking prizes in local shows.

In 1891 The Cottagers Garden Society Show was held in the ground of Grimsdyke. The lace and beadwork were well done. Winners for lacemaking were:-

Mrs M. Lacey

Mrs J Bowler

Mrs E Tomkins

Mrs E Turner

Mrs R Gibbons

Mrs J Currell grandmother to Daphne Bristow, lived at 2 Lime Tree Cottages, Kiln Lanel

Mrs A Floyd - grandmother to Harry, lived at Floyd's Farm

In 1892 at the Oxford Self Help Association, successful exhibitors from Lacey Green were:-

Mrs Moses Hawes Eliza, mother of Nancy

Mrs Simeon Smith (coloured flax thread),related to Doug Tilbury

Mrs Devening

Mrs Tomkins

Mrs. Loosley

Mrs John Adams

Mrs John Currell (see above)

Taught lace to Connie Baker of Gomme's Forge.

She was originally a Maths teacher at Wycombe High School. She lived in Speen in a tiny cottage almost opposite Speen Weavers. After retirement she became very interested in bobbin lace making and visited as many old local workers as she could finding out the techniques involved in the craft. Her Maths background was very helpful in reproducing the old patterns. She taught lace making at Wycombe College and other places for many years and was active into her old age. She also instructed a few young ladies at the High School, including myself. She was almost singlehandedly responsible for the revival of interest in lace making in this area.

Mrs. Edwards had learned lace making from Mrs. Joan Buckle of Prestwood. She came to the village to live in Hett's Orchard with her son in law and daughter. She was a very fine craftswoman and even made lace for the Queen. She demonstrated at many craft shows and taught lace making in the USA when visiting her son.

Jean lived in Lacey Green, then Speen, and now Naphill. She has taught many people to make lace.

Doris (mother of Rosemary Mortham) started to make lace in 1953. Like most modern lace makers she was interested in a great variety of crafts. She was taught by Miss Dawson, who had taught her maths at Wycombe High School many years before. She moved to Lacey Green after the Second World War and remembers seeing some of the old villagers making lace, including:-

Mrs Rixon, Mrs. Minnie Adams, Mrs. Kirby and her sister, Mrs. Redrup and her daughter.

Doris and her daughter were part of a fairly successful revival of bobbin lace making locally but only as a hobby. Sadly (as of 2009) even her generation are gradually passing on, and there seems little interest amongst younger people.

Rosemary still belongs to the Risborough Lacemakers. Anyone interested in learning lace making, or wishing to join the group is welcome to contact her on (01844 345863)

She is one of a few ladies in Lacey Green who are still able to make lace. The others include Mrs. Jill Baker and Mrs Eveline Lunn.

At least one lace school existed in Lacey Green and one in Loosley Row. This would have been just one room in a cottage and parents would have paid a small amount for their children to be taught. At such schools very young children, both boys and girls, spent all day working at their pillows. If they were lucky they might also have received a little tuition in reading and counting at the same time. They would learn little songs and rhymes "Lace Tells" to encourage them to work faster and some of these were semi - educational.

This somewhat bloodthirsty poem gives some idea of how hard the lives of children could be. The "rod at two" clearly shows that children who misbehaved would be beaten. The last two lines refer to the practice of calling out when a set number of pins had been used. In our villages the water table was too low for people to have wells. Instead, they had water tanks. Jumping in the tank was a common method of committing suicide.

Get to the field by one,

Gather the rod by two,

Tie it up at three,

Send it home by four,

Make her work hard at five,

Give her supper at six,

Send her to bed at seven,

Cover her up at eight,

Throw her down the stairs at nine,

Break her neck at ten,

Gather her to the well lid by eleven,

Stamp her in at twelve.

How can I make the clock strike one

Unless you tell me how many you've done?

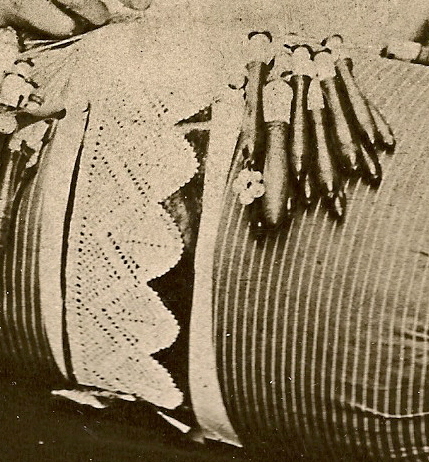

In our area, the local type of lace was the very fine and beautiful Buckinghamshire lace. This can usually be identified by the diagonal net, known as Bucks Point Ground. Lengths of lace would usually be straight on one side "the foot" for attachment to clothing etc., and shaped on the other, more decorative side, "the head".

The image, although poor quality, gives an idea of the design.

Bucks lace was slow to make and in the late 1800s many workers changed to Bedfordshire lace which is more open and faster to make. When this still did not prove profitable they made a coarse type of lace called torchon (dishcloth - in French). When they finally gave up lace making many local ladies took up tambour bead work, which was more fashionable in the early 1900s, being used on formal clothing like debutantes gowns. The centre for this work was Downley. (See article by Rite Probert on Tambour Bead Work.)

These could be homemade but were usually bought locally. There was a shop in Olney especially noted for their production.

South Buckinghamshire pillows, such as would have been used here, were bolster shaped and covered in hessian. They were stuffed with long pieces of wheat straw running along their length. This type of straw is rarely grown nowadays so other fillings have to be used. The straw was hammered down to ensure that it was very tightly packed. It was essential that the finished pillow was firm enough to hold the pins tightly. Eventually, the central (most used) part would become worn and the pillow would then have to be remade.

The whole pillow was covered in fabric; usually blue to show off the lace, or green, which was thought to be less trying to the eyes. Smaller cloths called "cover cloths" were used to cover the pillow where the work was proceeding to keep everything clean and to separate one batch of bobbins from another.

Bobbins and pillows were considered very personal items. They would normally be burnt when the user died. My mother was lucky enough to be given an old village pillow and bobbins which had been kept in a friend's attic, but she was told that she must never let anyone know where they came from.

In the South of Bucks these were all wooden, hand turned from local timbers, often fruit woods. They could be bought from local shops such as "The Bobbin Castle" in High Wycombe High Street, but usually they would be made by the men of the family using the same skills as were required by the bodgers in the local woods when making legs for Windsor chairs.

Their size varied according to the thickness of the thread being used. They needed to be heavy enough to hang down from the work in order to keep the thread taught. Around High Wycombe they were often decorated with inlaid bands or spots of different coloured wood. They could also be decorated with pewter bands and occasionally with small objects like buttons and shells. Some bobbins were made as a token of affection or for special occasions. When wooden bobbins are used they acquire a lovely shine from the grease on the fingers of the worker.

In the north of Bucks where mutton bone was sometimes used, bobbins were much finer. They were often marked with inscriptions or other decoration. As they were too thin to provide the necessary weight, circles of beads were wired onto their ends. Such bobbins are much collected now but I find the simple South Bucks bobbin much easier to work with.

The top section of the bobbin is like a tiny cotton reel and is used to wind the thread onto. The thread is held by a special knot to prevent it from unwinding while working. The worker does not need to touch the thread and so the work can be kept clean. Bobbins are used in pairs, which are often of a similar design.

Surplus bobbins were stored in small handmade wooden boxes. Most have bent hand made nails for hinges. The very early lace makers from the "low countries" had special compartments in their bible boxes to contain bobbins, so precious did they considered them to be.

These are not essential as thread can be wound onto the bobbins by hand but they certainly speed up the process. They look rather similar to small spinning wheels, with a wheel to turn the skein of thread, and a small vice like clamp to hold the bobbin.

Fine linen thread was preferred for Bucks Point lace. It is much stronger than cotton and less likely to break while working. Thicker thread known as gimp, could be used to outline the design. Modern workers have had to adapt to different types of thread as linen thread is very hard to obtain. Even for earlier workers it was imported and so would have to be purchased from a supplier or specialised shop.

Our villages are known to have been a source of "gold lace", probably using very fine brass wire. Whether any of the thread was truly gold I do not know. Certainly I have not been able to find any examples of such thread in the village, probably because it was too expensive to keep. There is an example (much tarnished) in Aylesbury Museum archives.

Towards the end of local lace making, villagers began to make a very coarse lace. It was made of a woollen thread called yak and would have been used for household purposes rather than clothing. I was given a sack full of bobbins by an old friend. Many were very large and had been used for this type of lace. Some were wound with coloured thread, which was also used in a bid to encourage sales.

Pin making was a specialised process. People in our area obtained their pins from Long Crendon where it was a cottage industry until the Industrial Revolution. Pins were made of brass so that they would not rust and mark the lace. The heads were applied by hand and were sometimes decorated with blobs of red or black wax or beads. The marked pins would show how much progress the worker had made in a set time and were called "strivers".

The patterns were known as prickings, since the position which the pins were to take was marked out by small holes made with a needle like "pricker". Again this was specialised work. Workers depended on a supplier to provide the template for the pricking. This work was mainly done by men. I remember re-pricking a much used pattern for a local worker as she had never learnt to do it herself. As South Bucks pillows were bolster shaped they were ideal for long lengths of lace, and short strips of pricking would be placed one after the other around them to make a continuous piece of lace, or a continuous length of pricking might go right round the pillow. This was sometimes overlapped at the ends leading to damage to the pattern in that area.

Prickings were originally made on vellum. Later a waxed card was used. Nowadays prickings can be made from photocopies of the original pattern. Some of the old patterns are held in High Wycombe and Aylesbury museums. They would have taken many hours to make and so were much cherished.

In the days before electricity this was a real problem. Even candles were expensive, so the light was magnified using a globe of water placed in front of the flame. In lace schools a number of globes were used so that several children could work around one candle. To make the best use of daylight lace makers worked outside their cottages. Even so, the fine work caused their eyesight to deteriorate.

Everyone in our villages must have suffered from the cold and yet it would have been impossible to manipulate the bobbins if the fingers were too cold. Dicky pots were used, which were simple clay pots with a handle. These were filled with hot embers from the fire and placed under the ladies long skirts and petticoats. They must have been rather a fire hazard!

These were wooden stands used to support the pillow while in use. The simplest ones stood at the back of the pillow and prevented it from rolling off the worker's lap. This is the type which my mother acquired from Lacey Green.

Those from the Lacey Green area show a great variety of patterns, which is surprising for such a small area.

Some samples are of a type of black lace popular in the mid 17th century. Obviously the villagers were still able to make it in 1880. Some of the Bucks Point laces are also using patterns popular a century before. The lace made by Mrs Harford and Miss Jenkins are truly old in style. However there are no examples of lace more than one and a half inches wide. Narrower edgings appear to have been introduced about 1840.

There are a few examples of Bedfordshire type lace, which would have been quicker to make. These include a common design known as "Town Trot".

Coloured torchon lace is included in the collection, and this appears to be peculiar to the village. I was shown an example of this by Mrs Daphne Bristow, who kept the Post Office at Bradenham. It was made by her granny, Mrs Currell.

There is one example of "gold" lace, which was reputedly made for the Duchess of York in 1895

Some of the samples bear the name of Mrs Bousfield, wife of the Reverend Bousfield, who lived in Loosley House.

See also 18th Century

Although first phrased in 1832 - To The Victor Go The Spoils - has always been the case, never more so than in 1066 when William seized everything. He rewarded those who helped him with various Manors and land ownership was thereafter at their behest.

(Legally all land still belongs to the Crown which, in practice, enables the Government to make compulsory purchases or, put another way, compensate you for its seizure.)

1823 was a significant time for this area when land was re-arranged to improve farming yield. There is a wealth of recorded information on the pre and post land divisions and ownership which the following articles set out to provide.Between 1808 and 1818 Lord Cavendish acquired a vast amount of the parish of Princes Risborough including much of the Manor (see The Demesnes of the Manor of Princes Risborough), Culverton Farm, Wardrobes Farm, Brimmers Farm, and Old House Farm amongst others.

All these farms had a share in the Open Field System, that is, divided into strips, which took up all the better land between Little Wardrobes Lane and Princes Risborough. (Tenants could leave their holdings in their wills but new tenants had to apply to the Manor Sessions to obtain a lease of their own).

Above this level ran the Common land where people of the parish could graze their animals, driving them up from the town towards the pond at Widmer Farm and onto the common that ran as far as the windmill and skirting Loosley Row and Upgreen (the part of Lacey Green where stand Portobello Cottages) and Lacey Green which consisted of the present Church Lane (there was no church at that time). Past Kiln Farm and Stocking Farm, which he had purchased, as far as Lacey Green Farm (the other side of Slad Lane) and Greames Farm (Grymsdyke)

At the time of these purchases the cost of estates was very low. The Napoleonic wars had brought many of the well to do onto hard times. Certainly Mr Thomas Grace, the Lord of the Manor was on the verge of bankruptcy. Lord Cavendish was a member of one of great families of the land, and one can only assume that he was in a position to borrow money from within the family. All through the centuries land was purchased with borrowed money. And it is quite usual for wills to include provision for paying off mortgages or leaving money lent out on mortgage to an heir.

Backed by his huge amount of land, only John Grubb had more, Lord Cavendish set about getting other land owners to back a scheme to apply to Parliament for the parish to be Enclosed.

It took some time to get agreement and to get it passed but in 1823 the Enclosures here were completed. (See the Case for and against below).

The inclosure would ultimately prove of considerable advantage to the parish by giving more employment to the labouring poor - to the country by affording the means of increase in the product of the soil - and to the individual landowners and their tenants by uniting property at present greatly dispersed, and by freeing the whole from commonable rights and the payment of tithes. All at moderate expense.

The lands are dispersed and may be laid together. Good roads will be made. The tithes will be extinguished. The lands being made entire may be managed more to your mind, and being compact the expenses of management will be decreased. The waste land now producing but very little will become valuable land. All questions and disputes about tithes will be set at rest. The inclosure may be carried out at moderate expense. Exchange may be made greatly to the convenience of the proprietors. The wastes would afford employment to the labourers for many years.

A chapel will be erected at Lacey Green and much advantage may be expected of it."

The Reverend Meade "much good may probably be done for the spiritual improvement of that almost heathen district".

The Reverend Richard Meade, perpetual curate of Princes Risborough had long wished to build a 'Chapel of Ease' for the Upper Hamlets (Speen, Lacey Green and Loosley Row). He had applied frequently to the Society for Promoting and Enlarging Churches and also to the Bishop of Lincoln in whose Diocese it was. This idea was long known and approved by the habitants of the district. He had arranged some time before with John Grubb that he would donate 10 acres, who on Enclosure relinquished part of his claim to Cavendish. "This could be effected by the benefaction of the nobility and gentry. The Curates stipend could be raised by

The bounty was originally funded by the annates monies: a tenth of the income each year traditionally paid by English clergy to the pope until the Reformation and thereafter to the Crown - Henry VIII.

Queen Anne's Bounty was a scheme established in 1704 to use this money to augment the incomes of the poorer clergy of the Church of England

"Some of the richer proprietors seem disposed to assist in the undertaking."

1819 - Meade writes to the 'Commissioners for New Churches' for advice and suggests a meeting to better arrange how to act respecting this very desirable object that will certainly improve property thereby.

Never known any good arise from Inclosure.

The expenses will run away with the land.

The poor people, who keep 1 or 2 cows each, have a small meadow for grass (for hay) and the run of the Commons for pasture will be ruined.

The small farmers who have the walk (on the Common) for their flocks will never be able to keep a sheep after the inclosure.

There is little doubt that enclosure greatly improved the agricultural productivity of farms from the late 18th century by bringing more land into effective agricultural use. It also brought considerable change to the local landscape.

Where there were once large, communal open fields, land was now hedged and fenced off, and old boundaries disappeared.

The common people were up against the landed gentry and the church at a time when the Church had strong influence. Unsurprisingly the inclosures did take place and both sides proved to be correct. That is to say all things predicted by those "for" actually happened. Those "against" were also right in foreseeing that the villagers would become impoverished. Their way of life changed for ever.

But historians remain divided over the extent to which enclosure forced those at the lowest end of rural society, the agricultural labourers, to leave the land permanently to seek work in the towns.

The cost, another thing in the "against" case was defrayed by some landowners giving land to the Commissioners to sell.

The Church Tithes were replaced with Glebe1 fields which could be rented out.

Lord Cavendish put Stocking Farm up for sale in 1827. It was bought by Charles Brown the following year. The other components of his estate were put up for sale between 1846 and 1854.

The way of life here was changed for ever. ( See Rural England pre 1823) No doubt the standard of farming improved but the cottagers, who were never rich but had managed before, were now impoverished. The Enclosures became for many, a taboo subject.

1Tithe = Plot of land belonging to an English parish church or an ecclesiastical office.

Notes made by the late Rex Leaver with kind permission of Mrs Leaver.

1819

June 1st Pinder Simpson, representing Cavendish wrote to John Grubb proposing enclosure. Grubb,Tindall and Collison discuss terms which are proposed to Cavendish and Holloway.

August. Tindal tells Winslow of intention. Winslow and his friends form an opposition committee and call a public meeting. The meeting passes resolutions against enclosure which 93 sign. Not sufficient to pass the proposal.

September 12th "Tumultous mob" prevents posting of notice of intention to enclose. Five arrested. Committee members stand bail for them. Two more postings on the church door are protected by special constables. Church door notice of intention to oppose signed by 20. Tindal appoints Ellis as parliamentary agent and prepares petition to commons.

November. Tindal finalises with Ellis petition for leave to bring in a bill. Land proprietors canvassed to sign petition and/or withdraw opposition. Canvassing continues - pressures brought to bear on small proprietors. Opposition counter campaign and enlist interest of Nugent as well as Rickford, two local M.P.s. Tindal consults Ellis over technicalities of proceeding.

December 9th Petition presented and House of Commons gives leave to present bill.

1820

Jan At quarter sessions the rioters plead guilty. Given small fines.

Jan 29th. George III dies, creating uncertainty about validity of petition.

Feb Grubb doubtful about proceeding and upset by Nugent's rumoured opposition. Holloway against further delay. Simpson brushes aside doubts.

March. Parliament dissolved. General election. Nugent and Rickford unopposed

Cost estimates made to appease opponents. Who print statement against.

April 27th New Parliament meets, fixes timetable. Ellis says a new petition is needed. Tindal arranges printing of bill and acquires opponents` statement

May 5th Second petition presented. House of Commons gives leave to bring in a bill.

May 22nd Winslow refuses offer to nominate a Commissioner. Grubb wavers again but agrees to go to a second reading when expense to be reconsidered. Promoters agree details of a draft bill and attempt to conciliate opposition. Promoters lobby influential absentee proprietors

May 31st. First reading of enclosure bill Promoters canvas 150 proprietors near and far for consent signatures.

June 6th Second reading of bill after petition from opponents. Promoters lobby 100 M.P.s Attempt at technical defeat of Bill fails. Sent to Committee. Canvassing continues. Promoters change basis for measuring support.

June 21st Favourable Committee report after evidence from both sides. Third Commons reading and readings in the Lords

June 30th Royal Assent given to bill.

The Reverend Richard Meade, perpetual curate of Princes Risborough, had long wished to build a Chapel of Ease for the Upper Hamlets (Speen, Lacey Green and Loosley Row). He had applied frequently to the Society for Promoting and Enlarging Churches and also to the Bishop of Lincoln in whose Diocese it was.

This idea was long known and approved by the habitants of the district. He had arranged some time before with John Grubb that he would donate 10 acres, who on enclosure relinquished part of his claim to Cavendish.

"This could be effected by the benefaction of the nobility and gentry. The Curates stipend could be raised by "Queen Anne`s Bounty"

"Some of the richer proprietors seem disposed to assist in the undertaking."

1819

Meade writes to the Commissioners for New Churches for advice and suggests a meeting to better arrange how to act respecting this very desirable object"that will certainly improve property there by civilising a set of rustics far distant from any place of established worship more than almost anything I know of."1820

29th May. The Commissioners of Queen Anne's Bounty state that they will give £300 if Meade can obtain £200. Three tithe owners already have £50 each paid on their lands. Meade asks them to donate it to the fund. He, himself proposes to chip in £50. All is prepared.10th June Letter -

Governors of "Queen Anne's Bounty approve this curacy as proper for further augmentation by benefaction from the Parliamentary Grants You will therefore be pleased to cause the benefactors £200 to be paid to their Treasurer.29th June With promises of £500 available The Reverend Meade just needs a site and all is ready.

1823

The enclosure Commissioners make an allotment to The Reverend Richard Meade on which to construct a Chapel of Ease with graveyard.

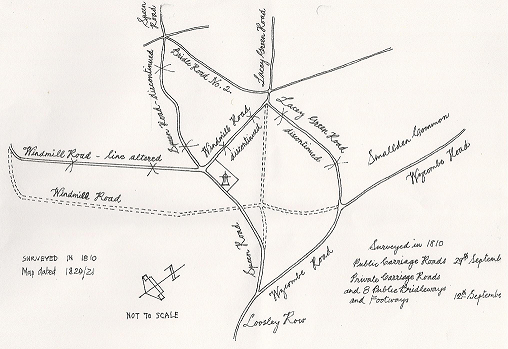

A survey of the roads in Lacey Green and Loosley Row was completed in 1810, although it was not published until 1820/21 two years before the Enclosures were implemented.

By then the Speen Road had been extended from the end of Highwood Bottom straight across the Hillock to behind the windmill. At this point was a crossroads. Windmill road coming in from Parslows and turning towards Lacey Green village and the Lacey Green Road. Speen Road carried straight ahead to join the Wycombe Road where it turned down into Loosley row.

Where Lacey Green Road met Windmill Road it turned down into Loosley Row to meet up with the Wycombe Road at what is now the bottom of Loosley Hill. The bridleway from the end of Highwood Bottom up to Goodacres Lane was still there.

It was proposed that Speen Road would end at the end of Highwood Bottom and the Windmill Road would be discontinued, effectively removing the crossroads behind the windmill and the roads across The Common. (New roads shown in dashes)

Lacey Green Road went from the top of Woodway straight up and into Lacey Green. A new Windmill Road was to be made on the line of what is now Pink Road. This crossed the new Lacey Green Road at The Whip and down what was to become Loosley Hill. The existing Lacey Green Road would no longer turn down into Loosley Row.

Most of this was confirmed in the 1823 Enclosures Act. For more details and smaller additions see "Roads 1823"

A comparison of roads at the time of the local Enclosures with those today.

The main Turnpike road followed hereabouts the present day A4010.

Woodway Road from Loosley Row to the Turnpike at Dipton Bottom was as now, but junction onto A4010 altered for safety in 2008.

Wycombe Road leading from Loosley Row southward along the west side of the Hillock and Smallridge Wood, to the parish of Horsenden is today known as Lower Road, becoming Little Lane to the A4010.

Lacey Green Road leading from the top of the last described road over the said Hillock and Lacey Green to Dawes Lane, today comes from the top of Woodway straight up to the cross roads at The Whip and across into Lacey Green - the present Main Road.

Dawes Lane is now called Slad Lane.

Windmill Road leading from a lane near what was the Spratt public house at Loosley Row, crossing the Wycombe Road and Lacey Green Road and thence continuing over the Hillock to the parish of Monks Risborough. This route now starts by Gommes Forge, Loosley Row, up Foundry Lane to the top of Little Lane, across up Loosley Hill, across Lacey Green Main Road and along Pink Road to the Pink and Lily pub. Pink Road runs several metres off the crest of the hill on the Risborough side replacing Windmill Road.

Holloway Road leading from the end of Row Farm Lane and extending south eastwards along the Holloway to the Windmill Road. Today, read "Holloway Road leads from the end of Little Wardrobes Lane up to the Pink Road by the Pink and Lily pub."

Speen Road leads from the eastward end of Dawes Lane extending eastward to the southward corner of Wood Close; continuing by the eastward side of the said Close and to the middle of the road called Collway. Turning eastward along the said Collway and south side of Speen Green to the parishes of Hughenden and Monks Risborough. Translate this today as "starting at the east end of Slad Lane, by the entrance of the Home of Rest for Horses, proceed northward to the top of Darvills Hill, down to Flowers Bottom by the Plough pub then continue uphill round Devil's Elbow sharp bend to take you up to Speen and onwards to Hughenden or Hampden.

Brimmers Road leading from Horns Lane in and extending in a southwest direction along the west side of Burying Field to the Upper Icknield Way and after crossing the same along the east side of Old Windmill Field and the west side of Copt Hill Field to Brimmers Cottage and continuing in a southward direction along the bottom of the Hillock to the bottom of the Row Farm Holloway. Today the directions would be "from the junction with Horns Lane by Princes Risborough fire station proceed up New Road, cross the Icknield Way, pass Brimmers Cottage and continue straight ahead passed Brimmers Farm to the junction with Little Wardrobes Lane.

Walters Ash Road leading from the southwest end of a certain lane adjoining Grymes-Ditch Wood and extending in a south eastward direction over the east side at Beamangreen to Walters Ash Farm. Today you will find this little road starting on your left if you have turned down Smalldean Lane. It came out at Walters Ash Farm on the New Road at Walters Ash. In 1823 it was the route to Naphill.

From Lacey Green the route was round Slad Lane, across the present day cross roads (no New Road then) into Smalldean Lane, then left into Beamangreen by the recycling centre and along Beamangreen Lane coming out at Walters Ash Farm opposite the top of Bradenham Road. (There was no recycling centre in 1823.) Since then the RAF site has taken over most of this road, and there is no way through to Walters Ash.

Smalldean Lane went no further than the turning to Beamangreen Lane.

With the inclosures of land previously open to all; with the new allotments amalgamated together and crucially, the making of new roads, many places became inaccessible. It was necessary to establish connections to the properties. It was critical as to who was responsible for them and that the widths were fixed. It would prevent others encroaching on them as had been inclined to happen on The Common.

(Translated to modern language:)

XIV Road of the breadth of twenty feet leading from the north end of the Row Lane and extending on northward over allotments to Balliol College and James Crook to the eastward corner of an allotment to Lord George Henry Cavendish thence westward over the south side of allotments to the said Lord George Henry Cavendish to the Turnpike Road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the said allotments and of lands and tenements at Loosley Row for the time being for ever.

XV Road of the breadth of twenty feet leading from the last described road at Amen Corner in a northwards direction over the east side of allotments to the said Lord George Henry Cavendish to the southward corner of one other allotment to the Lord George Henry Cavendish for the use of the owners and occupiers of the said allotments and of inclosures near the said road now belonging to Peter Tyler and Jonathon Parslow for the time being for ever.

XVI Road of the breadth of twelve feet leading from the eastward of an old inclosure called Upper Manns belonging to John Ginger over an allotment to Peter Tyler nearly in the present track to the Wycombe Road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the same inclosure and of a collage and garden now belonging to James Crook for the time being for ever.

XVIII Road of the breadth of twelve feet leading from the eastward corner of an old inclosure called Great Coombs in a north east direction over the east side of Smallridge Wood and an allotment to John Grubb Esquire to the Lacey Green road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the inclosures and allotments for the time being for ever.

XIX Road of the breadth of twelve feet leading from a cottage and garden belonging to David Hadaway over an allotment to the said David Hadaway to the Lacey Green road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the same cottage and garden for the time being for ever.

XX Road the breadth of twelve feet leading from a cottage and garden belonging to Joshua Dell over an allotment to James Tilbury to the Lacey Green Road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the same cottage and garden and of the cottages and gardens adjoining for the time being for ever.

XXI Road of the breadth of twelve feet leading from a house and premises belonging to Francis Stone over the south side of an allotment to Joseph Lacey to the Lacey Green Road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the same house and premises for the time beig for ever.

XXII Road of the breadth of twenty feet leading from the Old Road at the west corner of an orchard belonging to Sarah Floyd by the westward side of an the the owners and occupiers of the allotments and inclosures near or adjoining the said roads for the time being for ever.

XXIII Road the breadth of twelve feet leading from the Old Road at the southward corner of an orchard belonging to John Dell in an eastward direction over the north side of an allotment to Sarah Shard to the westward corner of a garden belonging to John Hawes for the use of the owners and occupiers of the inclosures adjoining for the time being for ever.

XXIV Road the breadth of twelve feet leading from a cottage and garden belonging to Joshua Dell in south and east directions by part of the west and south sides of an allotment to Lord George Henry Cavendish to the Lacey Green Road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the inclosures and cottages adjoining for the time being for ever.

XXV Road the breadth of twelve feet leading from a cottage and garden belonging to John Parslow over an allotment to John Grubb Esquire in south west and south directions by an old inclosure belonging to Ann Dell to the Lacey Green Road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the same cottage and garden and inclosure for the time being for ever.

XXVI Road of the breadth of twenty feet leading from the Speen road at Darvills Hill in the east and north directions by the north and west sides of allotments to John Lacey Edward Anderson and John Grubb Esquire to cottages and gardens at Turnip End, thence over part of the west side of the last mentioned allotment to a gate in Sears Wood field for the use of the owners and occupiers near or adjoining thereto for the time being for ever.

XXVII Road of the breadth of twenty feet leading from an inclosure belonging to Edward Anderson over an allotment to John Grubb Esquire to the Speen Road for the use of the owners and occupiers for the time being for ever.

XXVIII Road of the breadth of twenty feet leading from Speen Road to the homestead belonging to John Roupell for the use of the owners and occupiers of the same homestead for the time being for ever.

XXIX Road of the breadth of twenty feet at the least leading from the Speen road at a cottage belonging to Frances Stone in the northward, eastward and southward directions by and between divers allotments and inclosures at Speen to the Hampden church. Road for the use of the owners and occupiers of the allotments and inclosures at Speen near or adjoining thereto for the time being for ever.

Leading from the north corner of High Wood over the eastward side of the Poors Allotment to the Windmill Road at Parslows for the use of the owners and occupiers of the near or adjoining thereto and of Monkton Wood in the parish of Monks Risborough for the time being for ever.

XXXIV Road or Woodway of the breadth of twenty feet leading from the eastward end of the Hampden church Road in a southward direction over the east side of Abbotts Wood in its present track to the westward end of the Speen Road. Which said road is set out for the use of the owners and occupiers of the woods adjoining thereto and of Monkton Wood for the time being for ever.

XXXVIII Road of the breadth of twenty feet leading from Dawes Lane over part of the south side of an inclosure belonging to the said Lord George Henry Cavendish to the south west corner of Wades Grove for the use of and to be kept in repair by the owners and occupiers of Wades Grove aforesaid for the time being for ever.

(See also 20th Century Water Supply Connection)

As piped water did not come to the district until 1934 public ponds were vital. Water was supplemented by rainwater collected off the roofs in underground tanks. All properties had or shared a water tank. There were also a number of small private ponds. These were dependent upon the rainfall and also if they had been puddled with clay to seal the bottom. This was an art that has virtually died out.

Listed as ponds or watering places with details of access after Enclosure:

(described in modern day language.)

This pond at Widmer Farm on the Pink Road was the first pond where livestock could be watered when they were driven up from Princes Risborough to graze on the Common. Known as a Keeching pond.

No. 2 Timor Pond on the Hillock in an allotment sold to the said John Grubb containing twelve perches with a footway thereto of the breadth of six feet from the public footway.

This pond was behind the Windmill Farm at the old cross roads which had been discontinued in 1810. The footpath mentioned starts by the Whip pub by the bus stop and continues diagonally across towards Hampden.

No. 3 White Washings at Lacey Green in an allotment to the said John Grubb containing eighteen perches with a road thereto of the breadth of twenty feet from the Lacey Green Road.

This pond was down Kiln Lane and was incorporated into a garden in the 1970s after houses had been built round it. It was kept for animal use.

No. 4 Deep Pit in the same allotment as the above near the Brick Kiln containing twenty four perches.

This aptly named pond is still to be found down Kiln Lane. This was kept for human use. Lime was put in it to keep it pure. It is understood that a horse and cart sank out of sight in it.

No. 5 Near Stockings Farm homestead at Lacey Green in an allotment to the said Lord George Henry Cavendish containing eight perches with a road thereto of the breadth of twenty feet from the Lacey Green Road.

During the second world war a group of people came from London to do 'war work' on the farm. They were put to clean out the pond. Unfortunately they broke the clay cap that seals old ponds so that it no longer holds water.

No. 6 At Lacey Green near or adjoining to the Lacey Green Road and the allotments to Thomas Stone and Ann Dell containing four perches.

This small pond has been filled in and a house built there.

No. 7 At Lacey Green in an allotment to Joseph Lacey containing thirteen perches with a private road thereto from the house and premises of Francis Stone of the breadth of twenty feet and a public footway thereto.

This pond is now in the garden of Gracefield. It was privately purchased by Hans and Peggy Jourdan when they lived there mid nineteen hundreds, also the road to it.

No. 8 At Turnip End adjoining the private carriage road of the breadth of twenty feet from the Speen Road at Darvills Hill to Turnip End containing six perches.

This pond is still in the hamlet of Turnip End. The private carriage road is now public but not adopted by the council.

And we the said commissioners do hereby order direct and award that all and every the said private carriage roads herein set out and appointed shall be made and at all times hereafter be supported.

The Enclosure Commissioners had spelt out exactly how the Parish Open Field, the Common land and the waste land was to be divided and to whom it was given. New roads were built. They had designated certain ponds to be for public use and given them access. Every new inclosure had the responsibility for its boundary stipulated (especially important when neighbouring lands met). Wherever possible the land was given in proximity to land already owned to make bigger holdings. Some land was given up to raise money to pay for the Commissioners. Some was exchanged, some was sold.

These field boundaries, new in 1823, are, by and large, still the same in 2009.

In Loosley Row and Lacey Green life was changed. The major landholders had enlarged the farms they owned. These had been, and continued to be, let out. Smaller landowners had allotments according to how many strips they had had in the Parish Open Field and their percentage rights on the Common and of the grassland in the valley. Allotments in lieu of this were given, as near as possible, to their existing land. The cottagers who had no land but had scratched a scanty living from their gardens, maybe kept a pig there, used the Common probably without any legal right, perhaps also earning a little at harvest time when extra labour was needed and going gleaning on the stubbles, were now in dire straights. These independent minded people now needed to be employed. They didn't take to it kindly.

However there was much work to be done if a whole season in this agricultural community was not to be lost. The Parish Open Field had been divided between the bigger farms near it. Nothing could be grown there until the strips and the coarse grass divisions had been ploughed up and cleaned of the rubbish growth. Smaller landowners had to adjust to their extra land. All the new allotments had to have field boundaries hedged. New roads had to be made, involving much stone picking off the fields. And there was a church to build.

So there was work in plenty. Landholders if possible did the work themselves or with their family. But many must have had to use paid labour. However none of this gave them any return - they had to get the land working.

For the first time ever all the land could be managed as the farmer saw fit.

This was a unique opportunity for those who were capable of taking advantage of it. "Management" was not something they had had much opportunity to practice. There had been a few enclosed farms which would have had some idea of it. Now they were much bigger.

It would have been gradual, new practices filtering down to such a rural place, where many were unable to read or write. But gradually it happened. The market would have been a wonderful place to exchange news and views. Then trial and error on your own land to see if it worked for you.

There were several major things that proved universally important. Keeping the crops weed free improved the quality of the crops and keeping stock, sheep and beef cattle to manure the fields improved the yield. Then by growing turnips for the sheep and mangol wurzels for the cattle and better grass for hay, animals could be kept through the winter, instead of most being killed and salted down. The seed drill planted the corn in straight rows that could be hoed with a horse drawn hoe. With hard work and an instinctive feel for their land they began to make it successful.

In 1823 there had been vast acres of woodland. These had been allotted out and before the end of the century they had virtually all been felled.

If before the enclosures the population had been asked their occupation they would probably have said "Landed proprietor", "Farmer", "Cottager" or a few specialist trades such as blacksmith, wheelwright, cobbler. By the middle of the eighteen hundreds there were still farmers but everyone else could declare an occupation. There were still the specialists but one in five were working in the timber industry whilst four fifths admitted to earning their living on the land.

The new system had been accepted.

Known as St.John`s, at Stone near Aylesbury, it was a mental hospital; not so much for the dangerous or insane; nor a place for those who were a bit simple who had their place in the villages where easy, useful jobs could usually be found for them; but more as a refuge for those who needed to get away from it all for a while.

Now in 2009 mental breakdown is a commonly recognised condition, more than likely treated with anti-depressants or "Take a Break", "Go on Holiday". That was virtually impossible to do in the days before state benefits for families, health and housing. It cost too much money to take a holiday, even if only to a relation somewhere in England.

Some times were more than usually difficult and for those who were really desperate suicide was a common option. St. John's opened in the early nineteenth century. It offered sanctuary from the world; a place where the pressure was taken off; a place to rest, relax and recuperate, and generally get away from the world. It was no health spa, in fact it was spartan, but people had their own room, could socialise in public areas and meet their visitors there.

People went there voluntarily. Many were those who drove themselves too hard when building up their own businesses or even had large businesses which got crushed or squeezed when their industry was in a slump, often through no fault of their own. It was just that at that particular moment, times were against them. Locally, building, farming and supplying the furniture trade in High Wycombe were particularly vulnerable to such fluctuations, and round here that is what most people did. It was one step forward and two back, many times.

Perhaps it was considered too spartan, but in 1980`s it was closed but not replaced. Perhaps mental breakdown became recognised and the National Health Service put it under the wing of the G.P's. But numerous hard working, socially active people benefited from a stay in St. John's, returning home to continue their useful lives.

The former St John's Hospital was built in 1850-1852 in the area of Stone in Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire. The building was designed by the architect David Brandon. In 1868-1869 a new chapel and two wards were added and two wings were added and the chapel was enlarged in 1902-1904 to designs by R. J. Thomas.

The hospital was originally built as the Buckinghamshire County Lunatic Asylum which it remained until 1919 when it became the Buckinghamshire Mental Hospital until 1948. The hospital specialised in providing care for people with psychiatric problems. The building was closed in 1991 and the land was kept for a housing estate. At some point after this the building was demolished and now no longer exists. All that remains of the original building are the staff houses and the asylum chapel.